In emergency management, we often assume that preparedness follows a continuous cycle—moving from assessment to planning, then to training and exercises, before looping back to assessment. This cycle is embedded in industry doctrine, taught in professional development courses, and used as a model for preparedness programs nationwide.

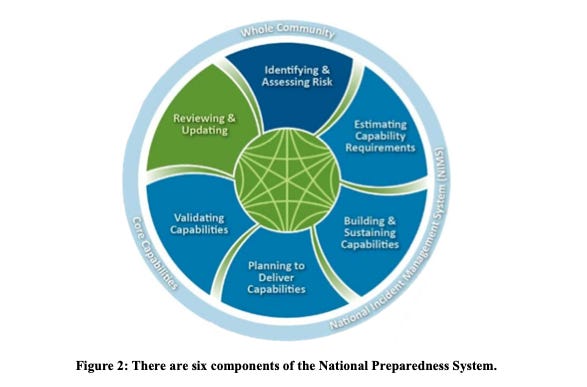

As an example, here are the six components of the National Preparedness System from the Department of Homeland Security's Comprehensive Preparedness Guide (CPG) 201, in a smoothly flowing circle (source).

But here’s the problem: by presenting preparedness as a seamless, repeating circle, we create a false assumption that this outcome is natural and inevitable. In reality, many preparedness initiatives fall short not because organizations failed to follow the cycle, but because the process didn’t move in a circle at all. Instead, it often resembles something else entirely—a square.

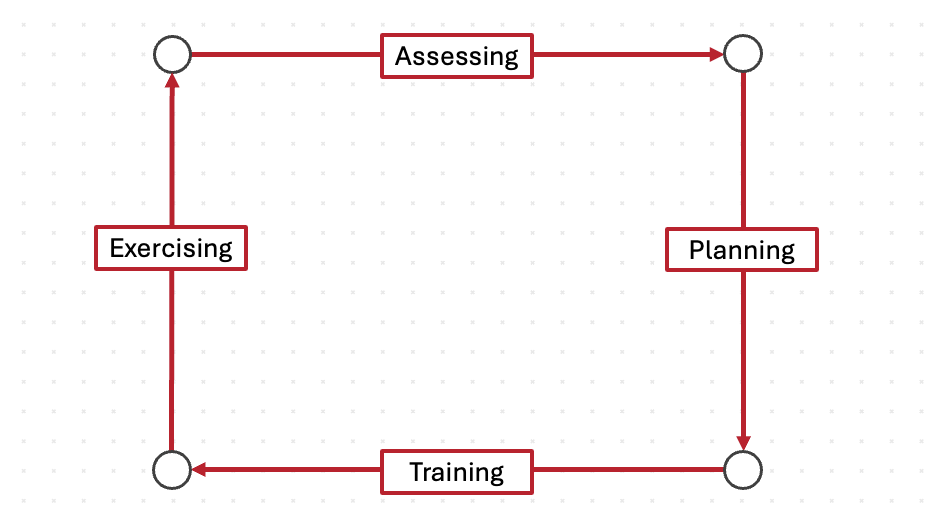

Why Preparedness Often Looks Like a Square

More often than not, preparedness initiatives unfold in a stepwise, compartmentalized fashion rather than as a continuous flow. If we break down the typical approach, it looks something like this:

Assessment – Emergency managers assess capabilities by reviewing documentation, engaging with key stakeholders, and analyzing gaps. Once the assessment is complete, they stop.

Planning – The focus then shifts to writing the plan, holding planning meetings, and finalizing the document. Once the plan is approved, they stop.

Training – Training programs are designed and delivered to relevant stakeholders. Once training is delivered, they stop.

Exercises – Exercises are developed and conducted to test the plan’s effectiveness. Once the exercise is over, the process stops again.

Rather than a smooth, circular flow, this process consists of hard stops and sharp 90-degree turns. In project management terms, this is known as finish-to-start sequencing, where each phase only begins after the previous one has fully concluded.

The problem? This rigid, first this then that approach leads to gaps in preparedness and missed opportunities for improvement because each phase is treated as independent, rather than as part of a continuous system. Even when organizations say that each phase builds on the last, the way these steps are actually executed often disconnects much of the learning that happens in one phase from influencing the phases that follow.

Insights from assessments and the lessons learned from incidents in other parts of the country don’t always shape planning discussions. Planning assumptions don’t always inform exercise objectives or the evaluation guides. And, by the time gaps are identified in training or testing, the window to refine earlier work has often closed.

For example:

If an assessment identifies critical issues identified in after-action reviews and lessons learned responding to similar incidents in other parts of the country, but those findings aren’t explicitly connected to planning discussions, the planning phase may overlook key vulnerabilities.

If a plan is developed without considering which elements will need to be tested in an exercise, and if those elements have not informed the exercise objectives or the evaluation guides, the plan may rest on unchallenged assumptions.

By the time an organization reaches the exercise phase, the original planning team has often disbanded, making it difficult to revisit and revise decisions made earlier in the planning process.

Because each phase is so often treated as a standalone project, changes made late in the process to one section of the plan—especially in complex disaster response plans—can have cascading impacts on other sections of the plan and risk inadvertently inserting inconsistencies into the plan. Yet, since there is often no structured mechanism in place to revisit earlier decisions, these inconsistencies often go unnoticed until a real-world emergency reveals them.

The result? Disaster response plans that don’t align with the actual demands of the crises they are meant to address.

How to Turn the Square into a Circle

The key to overcoming these challenges is to eliminate hard stops between phases. Instead of moving from one phase to the next in a stepwise manner, emergency managers need to blend phases together by overlapping the work, ensuring that the learning from one step informs and shapes the next.

In project management, this is known as start-to-start sequencing, where elements of the next phase begin before the previous phase has fully concluded. This overlap bends the sharp angles of the square, first into an oval and eventually into a true circle. I think of it as the weight of the deliverables from the follow-on phases pulling the line down and away from a 90-degree turn, or the heat generated by the friction of overlapping and often competing tasks making the line malleable.

This approach has several advantages:

Identifying gaps earlier – When the planning process begins with an annotated outline while assessment findings are still being structured, key insights are less likely to be lost.

Ensuring exercises reflect planning assumptions – By determining exercise objectives and the evaluation criteria during the planning process, organizations can identify the critical observations needed to validate the plan and test the right elements rather than checking a box on exercise planning.

Providing flexibility for adjustments – When training, planning, and exercises overlap, teams acknowledge the human dynamics of capability-building projects and create opportunities to refine the approach before committing to a final version.

However, this shift requires a mindset change—preparedness cannot be treated as a series of isolated projects but rather as a continuous, dynamic process.

Building the Skills to Overlap Phases

Successfully implementing this approach requires a forward-looking perspective—one that anticipates future needs rather than focusing solely on the step at hand. Here’s how emergency managers can develop this capability:

Gain Experience Managing the Full Preparedness Process

The more experience emergency managers have in assessments, planning, training, and exercises, the more they intuitively recognize gaps and interdependencies.

Experience fosters a big-picture mindset, making it easier to anticipate challenges before they arise.

Use a Playbook for Managing Preparedness Projects

A structured approach—like the project management playbook we’re building in our Academy—can help emergency managers efficiently navigate preparedness initiatives.

This ensures that time is spent on meaningful deliverables, not wasted on managing fragmented processes.

Set Expectations for an Iterative Process

From the outset, communicate that the plan will evolve as new information emerges.

Encouraging stakeholders to keep their notes and remain engaged minimizes the friction of revisiting earlier decisions.

Map Out Interdependencies Early

Before starting an initiative, identify how key elements (e.g., assessment findings, planning assumptions, exercise objectives) interconnect.

By making these dependencies explicit, teams can proactively address them throughout the project rather than scrambling to reconcile them later.

Conclusion

Preparedness should not be a series of disconnected projects, nor should we assume that a circular cycle is automatically present. Instead, we must recognize that the natural state of preparedness often resembles a square—compartmentalized and disjointed—if we don't intentionally look ahead.

The challenge is not just to complete each phase but to integrate them. By overlapping phases, anticipating needs, and structuring projects to allow for continuous refinement, we can create a preparedness system that is truly circular—fluid, adaptive, and effective.

If done well, we should also be building a strong disaster response capability for our communities and organizations.

Very clearly explained, Patrick. This applies to many fields, not just emergency management! Lots of industries pay lip service to "continuous improvement," but as people switch roles or leave the organization, previously-learned lessons are forgotten and old problems recur. A system for retaining institutional knowledge is vital, but almost never in place (or maintained).